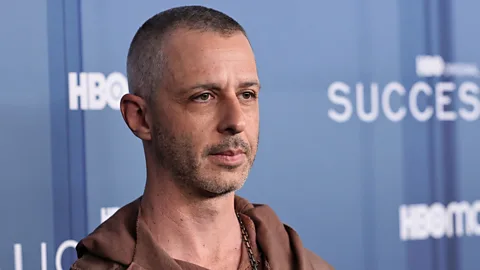

Jeremy Strong and Hollywood's most extreme actors

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs hit HBO drama Succession returns, star Jeremy Strong's "method acting" has been making headlines again. It's just the latest example of the performance style creating controversy, writes Hanna Flint.

No acting technique raises more eyebrows than method acting – commonly misunderstood these days to mean the style of performance where people go to extreme lengths to identify with their characters, or "get in their head".

More like this:

It's been in the headlines once again ahead of next week's premiere of the fourth and final season of Jesse Armstrong's eviscerating dramedy, Succession, thanks to renewed discussion around the divisive acting of one of its stars, Jeremy Strong. Ever since Strong discussed his tortured process for playing would-be media mogul Kendall Roy in an infamous 2021 New Yorker profile, he has been saddled with the "method actor" label. "I think you have to go through whatever the ordeal is that the character has to go through," he told the magazine. He also itted to isolating himself from his castmates, and sometimes refusing to rehearse because he wanted "every scene to feel like I'm encountering a bear in the woods".

HBO/Sky

HBO/SkyTo say his acting technique has been unpopular with his coworkers is an understatement. Castmates Kieran Culkin and Brian Cox both articulated their concern in the same article, despite what Cox described as the "tremendous" results the method had delivered. "I worry about the crises he puts himself through in order to prepare," said Cox. "I've worked with intense actors before. It's a particularly American disease, I think, this inability to separate yourself off while you're doing the job."

Recently, the classically trained Cox, who plays Strong's formidable father Logan Roy in the series, has been reiterating his distaste for Strong's extreme, often antisocial technique. He puts it down to the differing sensibilities between British and US performers. "It's really a cultural clash," the Scottish actor told Variety in an interview last week. "I don't put up with all that American s***. I'm sorry. All that sort of 'I think, therefore I feel'. Just do the job… Don't identify."

Despite the criticism, Strong has doubled down on his way of working. "Am I going to adjust or compromise the way that I've worked my whole life and what I believe in? There wasn't a flicker of doubt about that," he told GQ this year. "I'm still going to do whatever it takes to serve whatever it is."

What is method acting?

His contentious approach is the latest example of method acting causing controversy. Going "method" is typically seen as giving actors tacit consent to become their most antisocial and obsessive selves, so it's no wonder many stars continue to call it out: those who have had strong words to say on the subject range from Toni Collette to Mads Mikkelsen. Certainly, method acting has become a catch-all term for actors going to uncongenial lengths to bring authenticity and realism to their roles. However, just as Strong does not consider himself a method actor, as he told The New Yorker, it's important to differentiate the broad-brush conception of method acting in the public consciousness from the specifics of "The Method", argues Isaac Butler, critic, theatre director and author of The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act.

"People usually mean that they went deep into the research and never broke character on set," Butler tells BBC Culture. "Maybe they bought their own costumes and props and brought them with them. They wanted things to be as close to real life as possible – that's not The Method."

Method acting with a capital "M" is a series of inner techniques that use relaxation, and sensory and emotional exercises, as "a way of digging deep into the self in all of its idiosyncrasies and complexities to find the materials to make a character," says Butler. "To create a reality that they can live within as the character". There is in fact no one exact method to this naturalistic approach to acting but The Method is mainly associated with mid-20th-Century US director and acting coach Lee Strasberg – his institute once trademarked the name – who himself had been influenced by his peers Stella Adler and Sanford Meisner, as well as the forefather of naturalistic acting, Russian actor and director Konstantin Stanislavski. Stanislavski developed the idea of "perezhivanie" which, Butler writes, roughly translates to "re-experiencing", and "occurs when an actor is so connected to the truth of a role, and has so thoroughly entered into the imaginary reality of the character, that they feel what the character feels, perhaps even think what the character thinks".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs part of his so-called "system", Stanislavski developed the concept of "affective memory", whereby an actor would use "the sensory details of an intense emotional experience" to draw on those emotions in a controlled way for a scene, says Butler. Think of it like the Pixar movie Ratatouille; when the food critic Anton Ego tastes the titular dish, it triggers a happy childhood memory of the comfort of his mother's cooking. With affective memory, rather than relying on physical stimuli, the actor would aim to recall that taste, smell or sense, to re-experience the emotions of that memory, and use it to portray their character's similar emotional state in the required moment on stage or screen. "The actor doesn't fully become the character, that would be impossible," says Butler. "But the actor and the character instead meet so the actor's reality and the character's reality blend together".

When of Moscow Art Theatre introduced an early rendering of Stanislavski's system, focused on psychological training, to the US in 1923, it proved controversial. While Strasberg made affective memory a core principle of the process within his Group Theatre collective in the 1930s, renaming it "sense memory", Adler, a member of Strasberg's group before becoming an acting coach in her own right, wasn't as enamoured with the results. In 1934, Adler actually trained with Stanislavski in Paris in an updated version of his system because his earlier techniques had caused her anxiety as an actress. Rather than drawing on personal experiences and memories, Stanislavski taught her to create them using her imagination within a scene's given, sociological circumstances.

By 1947, The Actors' Studio was founded in New York by Elia Kazan, Cheryl Crawford, and Robert Lewis, and there, both Adler and Strasberg taught their differing methods with input from these founders. With TV shows shooting in the city, and Kazan commanding respect as a director across stage and screen, during the 40s and 50s the Studio became a "creative powerhouse", says Butler. "Your whole career could be made there and you're getting this amazing training, unlocking your emotional depths."

Actors like John Garfield, who had been part of the Group Theatre collective, were already deploying Method techniques in film before the rise of the Actors' Studio, but it was with the ascent to stardom of Studio alumni like Montgomery Clift, James Dean and Marlon Brando that method acting really became flavour of the month. Delivering human, viscerally charged performances in the likes of The Search (1948), Rebel Without a Cause (1955), and On the Waterfront (1954), respectively, these men unlocked a fragile masculinity in their troubled characters.

Certainly in the case of Brando, though, The Method specifically was not his method. "Strasberg liked to claim credit for people," says Butler. "He claimed credit for Brando who hated him." Adler was Brando's teacher, in fact, and helped him harness the required emotional nuances for any given scene as dictated from the script, rather than delve into his own psyche. But with his matinee-idol looks and rugged magnetism, the actor's screen presence revolutionised Hollywood, and certainly ushered in a more naturalistic approach to cinematic performance that has been, rightly or wrongly, aligned with The Method ever since.

Despite common misconceptions, though, great acting existed long before method acting materialised. "The obsession with method is also a misunderstanding of Hollywood film history," Vulture critic Angelica Jade Bastién tells BBC Culture. "People use it as a way to demarcate, 'oh, this is when acting really started in film'. There was a lot of really fascinating acting, pre-1950. Bette Davis remains untouchable, and she wasn't a method actor."

Davis was the opposite of a method actor: known for her intense delivery, she exaggerated her body and voice to portray the fluctuating emotional state of her characters with power and dignity. Even as the 1970s New Hollywood era favoured gritty realism, she understood her imagination was her most reliable fuel. "This film is a new experience for me," she said of the 1972 film Madame Sin. "For one thing, it's a crime fantasy, and usually I like to find some way of relating to my characters. But how can you relate to someone as outrageous as Madame Sin? So I have to invent all the time. It's fun."

Alamy

AlamyStill, with the likes of Al Pacino, Robert de Niro and Dustin Hoffman training with the Actors' Studio in the 70s, a new generation of stars renewed Hollywood's commitment to method acting. Hoffman, for example, lost 15lbs and ran up to four miles a day to get into shape for playing a PHD student and would-be marathon runner Babe in the acclaimed Nazi-espionage thriller Marathon Man (1976). When a scene called for his character to be out-of-breath, Hoffman would run half a mile before shooting so his exhaustion would be realistic. In the film, Babe finds himself on the wrong side of Nazi war criminal Dr Christian Szell, played by the classically trained thespian Laurence Olivier. The legendary story goes that when Olivier heard Hoffman had stayed up all night for two days before shooting scenes where his character had not slept for 72 hours, he allegedly told his co-star, "My dear boy, why don't you just try acting">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });